Examining FUHSD funding differences

Monetary spending at all five sites in the district is unique

Iman Malik and Brian Xu

When she started attending Fremont High School (FHS), she began to hear stereotypes claiming that it was a “ghetto” school. That the students there were slackers. That FHS wasn’t on the same level compared to other schools in the district. FHS sophomore and ASB Cabinet member Eleanor Paterson believes that due to its different socioeconomic standing when compared to the other FUHSD schools, FHS is often not given the respect she feels it deserves. For Paterson, these stereotypes became evident when she attended an inter-district conference for ASB.

“We all got to the conference half an hour early, we all set it up, we all cleaned it up, we all stayed after,” Patterson said. “We just tried so hard to make sure [FHS was] not perceived as ghetto, because it really isn’t. And it just kind of hurts a little when people still say that.”

According to FHS junior Trixie Rodriguez, MVHS has a reputation for being academically competitive and overbearing; many FHS students often characterize MVHS students as stressed because of their tendency to have heavy workloads and helicopter parents. Rodriguez believes that FHS does not foster an academically competitive environment, especially when compared to MVHS.

“For the most part, I think everyone is more community-focused,” Rodriguez said. “Academically, [FHS is] not the best, sports-wise, clubs-wise, it's not the best school. But I think FHS kids focus on getting better and they don’t focus on being the best. They focus more on growing. The only person you have to compete with is yourself.”

In 2019, Newsweek ranked the top 500 STEM schools nationally — MVHS ranks 69, Lynbrook HS ranks 87, Homestead HS ranks 102 and Cupertino HS ranks 106. FHS is the only school in the district that did not rank. Rodriguez believes that FHS is less STEM-focused because most students pursue what they are passionate about, rather than adhering to the stereotypical Silicon Valley career path.

“We have a lot of different departments at FHS, and people really care about what they’re involved with,” Rodriguez said. “I’m really involved with journalism, and I know the people in journalism really care about the paper. I’m also involved in theater, and people in theater put their heart and soul into it. And I think that’s true of everything on campus. It’s just not a collective thing. Everyone is passionate about their own thing, which is how the world works.”

In terms of funding for student activities and other functions within schools, FUHSD implements a discretionary budget for each school in the district. These budgets are managed by each principal and include funding for athletics, student activities, academic support and professional development opportunities. At MVHS in 2019, the general budget allocated for discretionary use was $392,000. According to Associate Superintendent Tom Avvakumovits, the district aims to have schools receive equitable funding so that no one school has far more funding than needed in comparison to other schools.

However, each school’s discretionary budget is not its only source of funding. Booster programs for athletic and music groups allow students to raise additional money to purchase items such as new helmets or uniforms for a sports team. In these cases, Avvakumovits notes that FUHSD tries to keep an equitable framework in mind and the district may supply additional funding to schools whose booster programs raise less money than others.

Despite this, there are still factors that contribute to potential differences in funding for sports teams and student activities. For instance, Lynbrook High School (LHS) receives approximately an additional $200,000 annually from the Lynbrook Excellence in Education. This independent nonprofit organization aims to “promote and support excellence in education at Lynbrook High School.”

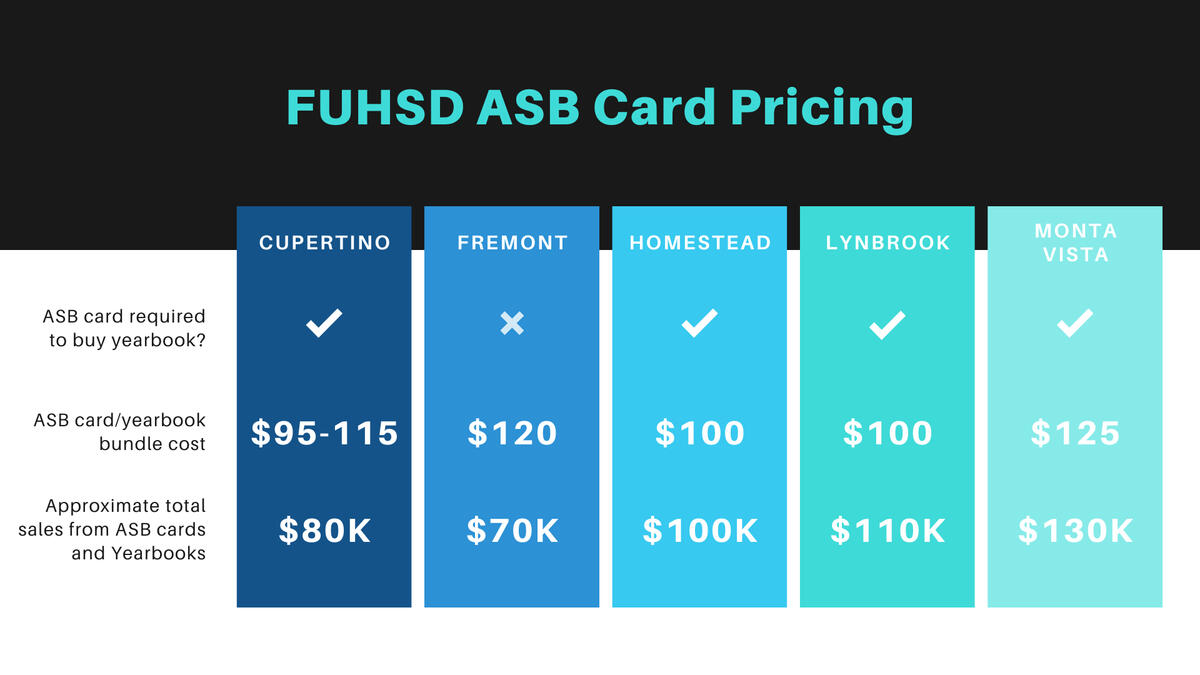

Due to differences in donations across FUHSD from sources like the LHS Foundation, Paterson believes there is a lack of funding for school clubs, programs and sports at FHS in comparison to other schools in the district. She attributes this mostly to the low number of ASB cards sold this year — therefore less money is raised for ASB at FHS. Paterson and Rodriguez say that because of the socioeconomic status of the student body (37% of students qualify for free or reduced lunch according to US News), buying ASB cards is not a priority.

In contrast, Superintendent Polly Bove and Avvakumovits believe the lack of ASB card sales can potentially be attributed to the categorization system FHS uses. At MVHS, an ASB card includes the yearbook. At FHS, however, students are allowed to buy their ASB card and yearbook separately.

Bove claims that the method in which the ASB card is sold matters — another school in the district previously had the same approach as FHS, but after changing it to the system MVHS uses, they saw an increase in sales. However, Bove also recognizes Paterson’s claim that the demographic of FHS may affect ASB card sales.

MVHS ASB cards/Yearbook sales reached 1,155 this year. Cupertino HS uses the same system as MVHS, and according to Avvakumovits, CHS sold 767 ASB cards this year. FHS sold 355 of the all-encompassing cards, 300 yearbooks only and 27 ASB cards. This equates to just under 700 cards — the fewest in the district.

Graphic | Brian Xu

“One of the things [the PTA parents] were finding is that because [FHS has] a larger newly [immigrant] population, that parents don't understand what it is or why their kids would want it,” Bove said. “So the PTA is really [making an] effort to help families understand why this is part of high school. And if you're new to the U.S., the culture of high school might seem a little odd to you.”

Paterson referred to this year’s ASB budget as inadequate — after looking at the ASB budget, she concluded that sports teams and extracurriculars were underfunded at FHS. Paterson is also on the FHS cheer team — in order to participate, she and other cheerleaders pay up to $3,000 per year. Although this amount fits into the national average of $2,500 to $10,000 per year, Paterson has seen several students drop out of cheer due to their inability to pay.

Similarly, Rodriguez, an editor for her school’s publication, notices the lack of funding for the journalism program. The FHS journalism program is operating with a $2,000 budget this year (which Paterson notes is not covered by ASB, but instead comes from the Fremont Union High Schools Foundation); at MVHS, journalism has approximately a $16,000 dollar budget with $6,000 raised by the students in the class through ad and subscription sales, $2,000 from the FUHS Foundation, $1,000 - $2,000 in other grant funding students and the adviser apply for each year and the rest covered by ASB.

Students pursuing extracurricular activities were not the only ones who had difficult financial circumstances, and Bove cites the complexities that come with amending financial inequity issues. According to Bove, FHS received Title I funding from the government around seven years ago. Title I is a federally funded education program that provides supplemental funds to schools with a high percentage of students from a lower socioeconomic status. However, Title I funding came with a complication for FUHSD. Receiving the funding requires strict standards of student performance, which Bove describes as near-perfect student test scores, an expectation that is unrealistic for any school in the district.

This led Bove to decide to no longer receive federal Title I funding — instead, the district rents one of its campuses to two schools from other districts and uses the revenue to fund FHS. FHS receives more funding than other schools in the district, though the additional funding is not allocated to student activities directly. In 2019, FHS received $440,000 from FUHSD for intervention classes (classes for students who need extra assistance with a subject) and programs designed to closely mirror how Title I funds are allocated. FHS is still eligible for Title I funding today.

“We go back and forth every year about deciding whether we're going to apply,” Bove said. “It's a very complex process to be a Title I school and frankly, it's very expensive. So it doesn't matter whether you get a lot of Title I funds or a little bit of Title I funds, you have to have almost a full-time release of somebody to make it happen.”

Despite the lower socioeconomic status of FHS students evidenced by the school’s Title I eligibility, Paterson believes FHS is a welcoming environment for students. This year, she has come to know a variety of new students from diverse backgrounds who have found comfort in the friendly FHS environment.

“FHS will always welcome anyone,” Paterson said. “It doesn’t matter if you came from St. Francis and you’re transferring in, or MVHS, or if you’re coming from Canada because we have a Canadian exchange student in Drama this year. It doesn’t matter where you come from, FHS is going to welcome you, no matter what.”

Both Rodriguez and Paterson are aware of the differences between FHS and the other schools in the district. However, they disagree with the “slacker” stereotype that they believe is often attributed to FHS. While some students may not be as academically driven, Paterson notes that many students spend time working after school to support their families.

“I would say that there are different things to base a school’s success on than academic,” Rodriguez said. “I know that’s what schools primarily focus on, [but] student quality of life and community [is] really important. And I’m not saying that FHS doesn’t care about academics. People work hard, and I think that having preconceived notions about our school is dangerous. It’s just that people care about different things here. Even though it seems to MVHS that FHS is a slacker school, it’s not.”

Additional reporting by Ishaani Dayal